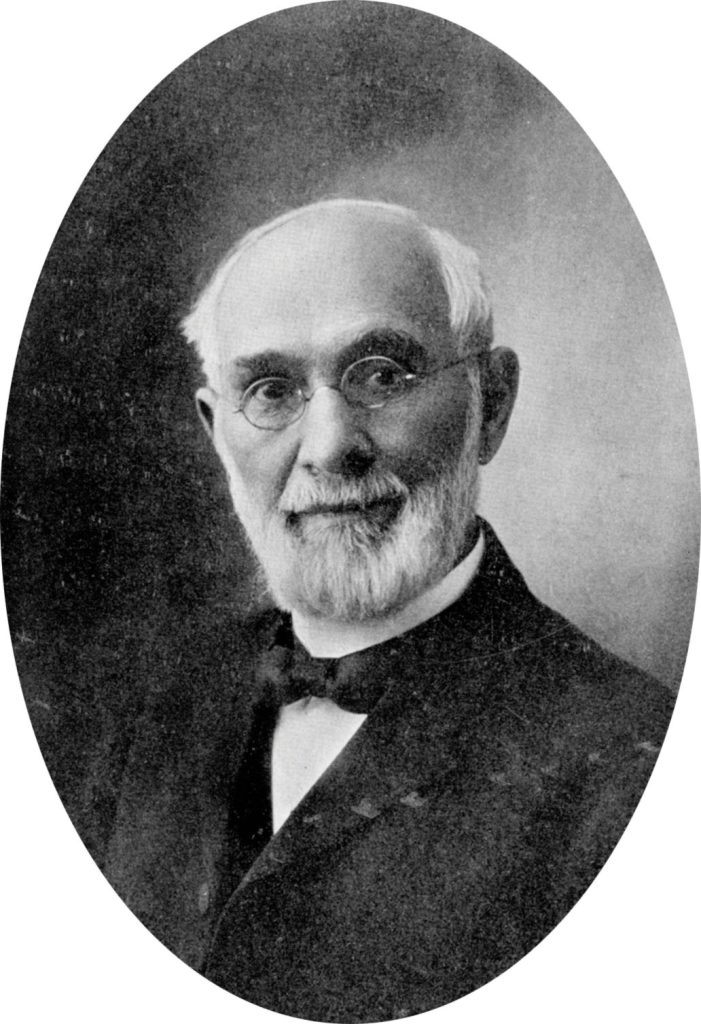

Allen Jay was a Quaker minister, educator, relief worker, evangelist and administrator. He worked here at Springfield Friends for 8 years after the Civil War, helping to rebuild the Quaker communities of the South.

He encouraged Quakers to revitalize our worship and helped start many new meetings. He worked tirelessly for spiritual unity among Friends. At the time of his death, historian Tom Hamm says he was “the best-loved Quaker in America.”

Early Life

Allen Jay was born in Miami County, Ohio in 1831, the eldest son of Isaac Jay and Rhoda Cooper Jay. His grandparents had moved to Ohio in the first wave of the great migration of Friends who left the South in the opening years of the 1800’s. Their primary motivation was a desire to disentangle their lives from the Southern economy dominated by slavery, and to live in the “free territory” which was rapidly being opened up in the Midwest. The family moved to a farm near Marion, Indiana in 1850 when Allen Jay was 19.

Education

Allen Jay was well-educated by the somewhat rough-and-ready standards of the time. He went to a one-room school in a log cabin a half-mile from his home. He studied for one term at the Friends Boarding School in Richmond, Indiana (which later became Earlham College) and at the Farmers Institute near Lafayette, Indiana. He also studied for a year at Antioch College, which had just opened under the leadership of famous educator Horace Mann.

The Underground Railroad

Quakers had decided in the late 1700s that members were not allowed to own or sell slaves, or buy, sell or in any way benefit from products of slave labor. In his Autobiography, Allen Jay describes a dramatic scene when he was about 13 years old, when he and his family helped an escaping slave to the next stop on the Underground Railroad.

Early Married Life

In 1854, Allen Jay married Martha Sleeper, the oldest daughter of the family he had boarded with while studying at Farmers Institute, and together they settled down to the life common to many young Friends of their generation. They bought a farm near West Lafayette, Indiana and had five children, expecting to spend the rest of their lives there.

Conscientious Objection

During the Civil War, the armies on both sides demanded more and more men, and conscription laws were passed to raise the required number of soldiers. The officer in charge of conscription came to Allen Jay’s farm and told him to report for training. Allen Jay refused to serve on religious grounds, and was told that he would be required to pay $300 to hire a substitute to serve in his place. Again, he refused, saying, ‘If I believed that war was right I would prefer to go myself rather than to hire someone else to be shot in my place.’

The officer returned again to auction off the Jay’s livestock and farm equipment in order to raise the $300. The threatened sale became a local cause celebre. Unknown to the Jays, their neighbors agreed that if the sale took place, they would buy everything at the auction and give it back to them. Finally, Governor Oliver Morton intervened personally with President Abraham Lincoln, who ordered the sale to be stopped.

Work for the Baltimore Association

Allen and Martha Jay moved to Springfield in the fall of 1868, where he became Superintendent of the Baltimore Association, a group of Quakers who wanted to help rebuild the communities of Friends in the South which had been shattered by the Civil War.

The Baltimore Association:

- rebuilt 60 elementary schools, provided books and school supplies, recruited Quaker teachers from the North, and ran a summer teacher training program for local Friends

- encouraged a new generation of Quaker ministers

- rescued Guilford College from bankruptcy, repaired its buildings, and provided scholarships for needy Quaker students

- created a Model Farm to demonstrate modern agricultural methods, and provided farm tools to replace the tools taken by the armies

Allen Jay worked with the hundreds of volunteers, organized programs and most importantly, helped raise the money which was needed for all the work to be done. He and his wife lived in the house across the road from Springfield Friends, which was the office and headquarters for the work.

Revivals and pastoral worship

During his time at Springfield, there were many revivals in the area, especially in the Methodist church. Allen Jay was concerned that the young Friends were being drawn to revivals and might leave the meeting, so he went to the revival in Trinity. He was invited to speak, and he asked the young Friends to stay at Springfield. He reassured their families, and many of the parents found a new depth in their own faith.

Over the next few years, many Quaker meetings in North Carolina and the Midwest adopted new practices, such as having a prepared message, singing hymns, and holding revival services. Allen Jay was largely responsible for the acceptance of these changes. Our worship today is based on the merger of the traditional “unprogrammed” Quaker worship with the new traditions he helped to pioneer.

Move to Earlham College

At the end of eight years in North Carolina, Allen Jay and his family moved to Providence, Rhode Island, where he served for four years as treasurer at Moses Brown School. Then they moved to Richmond, Indiana, where he worked for the next 30 years raising money for Earlham College, transforming it from a Quaker high school into a 4-year liberal arts college, creating an endowment and adding numerous buildings to the campus.

The Richmond Declaration of Faith and Friends United Meeting

In 1877, Allen Jay helped to organize a gathering of Quaker leaders from nearly all of the Orthodox yearly meetings in the United States. They met in Richmond, Indiana and created a document which was not a creed, but a strongly Biblical “statement of faith” which described Quaker beliefs. The Declaration of Faith was drafted in Allen Jay’s living room. Although the Richmond Declaration of Faith wasn’t adopted by all yearly meetings, it was included in many editions of Faith and Practice.

Over the next 20 years, Allen Jay helped to organize an association of yearly meetings which met every 5 years to support local and international mission work, publish Quaker news and encourage unity among Friends. The organization has grown and evolved and is now known as Friends United Meeting, with hundreds of thousands of members from around the entire world.

Senior Quaker Leader

Because of his outstanding ability as a fund raiser, Allen Jay was much in demand by struggling Quaker colleges. He raised money for Earlham College, Whittier College and Guilford College, and lent his support to Wilmington College, Central University and Pacific College (now George Fox University) as well as many local Quaker schools.

Thank you so much for this very interesting bio of Allen Jay, my great, great grandfather. This is very well written.

You’re very welcome! Have you read his Autobiography yet?

My first name is Jay, from my mother’s maiden name.

Alan Jay was my Great Grandfather. I have a treasured copy of his autobiography, from which I now am taking the time to learn what an inspiring and honorable man he was, of whom I am proud to be a descendant.

I would be interested in corresponding with any other historians in regards to knowing more about his life.

Thank you.

The original edition of Allen Jay’s Autobiography has been out of print for many years. If you haven’t seen it already, you might be interested in reading the new 2010 edition published by Friends United Press. It has a lot of footnotes and additional material which you might find helpful.

If you want additional resources, you might contact Tom Hamm (tomh@earlham.edu), retired professor of history and archivist at Earlham College. Allen Jay worked at Earlham for 30 years and many additional papers are there.